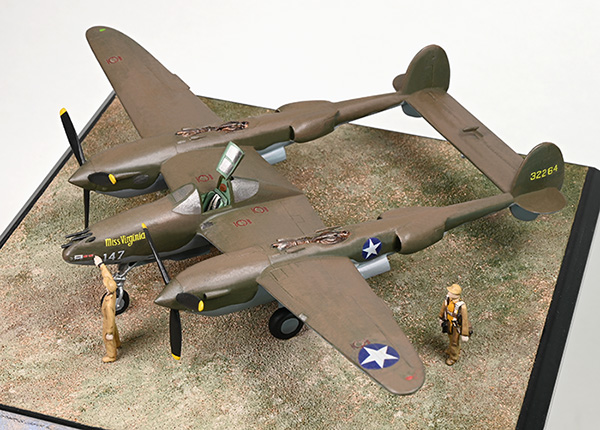

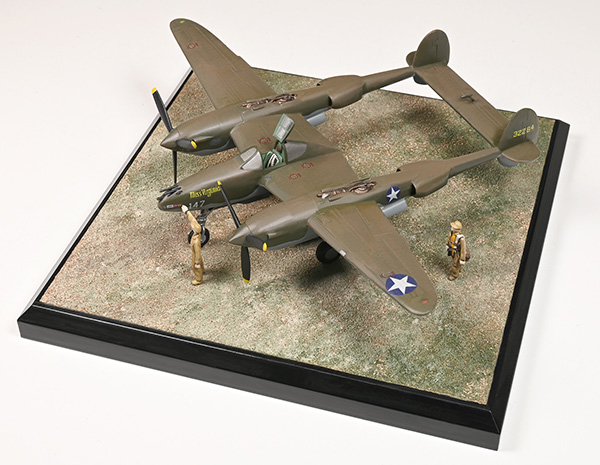

Lockheed P-38G-13

‘Miss Virginia’ ‘147′ 43-2264

Lts. Rex Barber & Bob Petit, 339th FS / 347th FG

Guadalcanal, April 18th 1943

The Lockheed P-38 was designed as a response to a February 1937 specification from the United States Army Air Corps. This was for a twin-engine, high-altitude “interceptor” having “the tactical mission of interception and attack of hostile aircraft at high altitude.”

The Lockheed design team, under the direction of Hall Hibbard and Clarence “Kelly” Johnson, considered a range of twin-engine configurations, including both engines in a central fuselage with push–pull propellers. Clustering all the armament in the nose was unusual American aircraft, which typically used wing-mounted guns with trajectories set up to crisscross at one or more points in a convergence zone. Nose-mounted guns did not suffer from having their useful ranges limited by pattern convergence, meaning that good pilots could shoot much further.

The Lockheed design incorporated tricycle undercarriage and a bubble canopy, and featured two 1,000 hp (750 kW) turbosupercharged 12-cylinder Allison V-1710 engines fitted with counter-rotating propellers to eliminate the effect of engine torque, this was achieved by the use of “handed” engines, which meant the crankshaft of each engine turned in the opposite direction of its counterpart. Turbochargers were positioned behind the engines, the exhaust side of the units exposed along the dorsal surfaces of the booms.

On 29 May 1942, 25 P-38s began operating in the Aleutian Islands in Alaska. The fighter’s long range made it well-suited to the campaign over the almost 1,200 miles (1,900 km)-long island chain, and it was flown there for the rest of the war.

The P-38 was used most extensively and successfully in the Pacific theatre, where it proved more suited, combining exceptional range with the reliability of two engines for long missions over water. The P-38 was used in a variety of roles, especially escorting bombers at altitudes of 18,000–25,000 ft (5,500–7,600 m). It was credited with destroying more Japanese aircraft than any other USAAF fighter

Since the Japanese surprise attack on ‘Pearl Harbor’ it’s architect Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto had been a prime target for the American forces. ‘Operation Vengeance’ was the codename given to the mission to find and kill Yamamoto .

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Imperial Japanese Navy, had scheduled an inspection tour of the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. He planned to inspect Japanese air units participating in Operation I-Go that had begun April 7, 1943; in addition, the tour would boost Japanese morale following the disastrous Guadalcanal Campaign and its subsequent evacuation during January and February. On April 14, the U.S. naval intelligence effort code-named “Magic” intercepted and decrypted orders alerting affected Japanese units of the tour.

The decrypt contained time and location details of Yamamoto’s itinerary, as well as the number and types of planes that would transport and accompany him on the journey.

The decryption revealed that Yamamoto, now given the codename ‘Dillinger’ by the Americans, would be flying from Rabaul to Balalae Airfield, on an island near Bougainville in the Solomon Islands, on April 18th. He and his staff would be flying in two medium bombers (Mitsubishi G4M Bettys of the Kōkūtai 705), escorted by six navy fighters (Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters of the Kōkūtai 204), to depart Rabaul at 06:00 and arrive at Balalae at 08:00, Tokyo time.

Eighteen P-38s of the 339th Fighter Squadron were assigned the mission. One flight of four was designated as the ‘killer’ flight, while the remainder, which included two spares, would climb to 18,000 feet (5,500 m) to act as top cover for the expected reaction by Japanese fighters based at Kahili. The 339th would wave-hop all the way to Bougainville to intercept Yamamoto’s flight at altitudes no greater than 50 feet (15 m), maintaining radio silence en-route.

In preparation for the mission, the P-38s were fitted with a navy ship’s compass to aid in navigation at the request of Major John W. Mitchell, commanding the 339th. The fighters each mounted a standard armament of a 20 mm cannon and four .50-caliber (12.7 mm) machine guns, and were equipped to carry two 165-US-gallon (620 L) drop tanks under their wings. A limited supply of 330-US-gallon (1,200 L) tanks were flown up from New Guinea, sufficient to provide each Lightning with one large tank to replace one of the small tanks. Despite the difference in size, the tanks were located close enough to the aircraft’s centre of gravity to avoid any performance problems.

Although the 339th Fighter Squadron officially carried out the mission, 10 of the 18 pilots were drawn from the other two squadrons of the 347th Group. The Commander AirSols, Rear Admiral Marc A. Mitscher, selected four pilots to be designated as the “killer” flight:

Capt. Thomas G. Lanphier, Jr.

Lt. Rex T. Barber P-38G ‘Miss Virginia’

Lt. Jim McLanahan (dropped out with flat tire)

Lt. Joe Moore (dropped out with faulty fuel feed)

Mitchell and his force arrived at the intercept point one minute early, at 09:34, just as Yamamoto’s aircraft descended into view in a light haze. The P-38s jettisoned the auxiliary tanks, turned to the right to parallel the bombers, and began a full power climb to intercept them.

Mitchell radioed Lanphier and Barber to engage, and they climbed toward the eight aircraft. The nearest escort fighters dropped their own tanks and dived toward the pair of P-38s. Lanphier, in a sound tactical move, immediately turned head-on and climbed towards the escorts while Barber chased the diving bomber transports. Barber banked steeply to turn in behind the bombers and momentarily lost sight of them, but when he regained contact, he was immediately behind one and began firing into its right engine, rear fuselage, and empennage. When Barber hit its left engine, the bomber began to trail heavy black smoke. The Betty rolled violently to the left and Barber narrowly avoided a mid-air collision. Looking back, he saw a column of black smoke and assumed the Betty had crashed into the jungle. Barber headed towards the coast at treetop level, searching for the second bomber, not knowing which one carried the targeted high-ranking officer. Capt. Thomas G. Lanphier, Jr. successfully dispatched the second Betty.

The P-38G-13 ‘Miss Virginia’ of Lt. Rex Barber was shared with Lt Bob Petit who had sunk a Japanese ship flying ‘Miss Virginia’ on the 29th of March. Barber had shot down two A6M2 Zeros off Cape Esperance on the 7th of April.

The death of Yamamoto raised morale in the United States and shocked the Japanese, who were officially told about the incident only on May 21, 1943. In the United States, in order to cover up the fact that the Allies were reading Japanese codes, American news agencies were given the same cover story used to brief the 339th Fighter Squadron—that civilian coastwatchers in the Solomons observed Yamamoto boarding a bomber and relayed the information by radio to American naval forces in the immediate area. This convinced the Japanese military that it was only through a stroke of luck that the Americans carried out the successful attack.